Showing posts with label Released: May 2011. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Released: May 2011. Show all posts

REVIEW: DVD Release: The Warrior And The Wolf

Film: The Warrior And The Wolf

Year of production: 2009

UK Release date: 30th May 2011

Distributor: Universal

Certificate: 18

Running time: 101 mins

Director: Zhuangzhuang Tian

Starring: Maggie Q, Jô Odagiri, Tou Chung-hua

Genre: Action/Drama/Fantasy

Format: DVD

Country of Production: China/Hong Kong/Japan/Singapore/USA

Language: Mandarin

Review by: Rob Markham

Glorious landscapes and grandiose battles come as standard with the Chinese epic. From Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon to Hero, we have been dazzled by their beauty. The Warrior And The Wolf is a much more cerebral take on the genre, mixing the scale of the epic, the battles and the politics with an element of the supernatural.

Set during a time of vicious battles between the Imperial Court and various nomadic tribes in the borderlands of China, The Warrior And The Wolf tells the story of Lu, a peaceful shepherd who joins General Zhang’s army.

Initially scared and unwilling to kill, Lu rises through the ranks to become one of the most fearsome warriors in the army, and when General Zhang is taken prisoner by one of the tribes, Lu negotiates his release by trading the son of the tribe’s prince for his General.

When the General is sent home injured, Lu takes command of the army and leads them on the journey home when the snow comes. The heavy snow makes the journey impossible and the army must take shelter in a village occupied by the Harran tribe. The Harran are supposedly cursed, and when a sexual relationship forms between Lu and a beautiful widow, the curse is revealed.

Years later, General Zhang returns to the borderlands to deliver the Imperial Edict detailing the tribe’s surrender. When two of his men shoot at two wolves and are found dead later that night, a hunt ensues…

Initial expectations and the opening captions of The Warrior And The Wolf would seem to suggest that we are entering the realm of the epic. However, if you are expecting this to be in line with Chinese epics such as House Of Flying Daggers and Hero then you will be disappointed. Instead of the grand opulence of these films, The Warrior And The Wolf is a much more thoughtful, emotive film, short on dialogue and relying on camerawork and acting talent to convey meaning and emotion. Where in other, similar films, there would be vast battles, bathed in colour, here the few battles there are seem small in scale compared to the vast landscape on which they are played out, and the palette is very subdued, heavily reliant on autumnal and winter green, brown and white, rather than a rich, theatrical colour-scheme. The star of the show here really is the Chinese landscape. Throughout the film, we are treated to some breathtaking shots of snow covered mountains and the borderlands in spring. There is a very strong contrast between the barren and the vibrant, clearly echoing the sense of isolation the soldiers in the outpost must feel.

The performances are also of a high standard. Jo Odagiri begins suitably innocent and, under the circumstances, does a good job of conveying what it is like to lose one’s humanity through violence, using little more than facial expression and body language. Though she is given little to do, Maggie Q makes the most of a largely thankless role, and Tou Chung-hua is pitch perfect as the battle-weary General.

It’s a shame, then, that with these considerable assets, the film does not offer us much else. It is clear that director Zhuangzhuag Tian is trying to convey a more thoughtful story through his use of internal struggle, which, while played superbly by the cast, never translates into anything truly meaningful over the course of the film. Despite Odagiri’s fine performance, the character of Lu does not fully convince in his journey from peaceful shepherd to warrior, as the transition is given little development in the first act. Flitting back and forth between the past and present, we see some evidence of Lu’s compassion (his bond with a wolf cub), his cowardice (running from a training session in which he must kill a prisoner) and then his transformation proper, with a bloodthirsty rant at prisoners of war later on, but the transition is unconvincing and sorely undersold and, as a result, his place as a respected warrior is never solidified in the mind of the audience.

This problem of underdevelopment is most notable in the relationships in the film, as it would seem character development was ignored in favour of sweeping shots of the landscape and some truly awful FX work. The bond between Lu and the wolf cub is not highlighted with any real significance, despite its importance to later events; the bond between Lu and General Zhang is never allowed to breathe, and their relationship appears devoid of any meaning; and the relationship between Lu and the Harran widow turns from rape into love seemingly overnight. There are important points to be made with each of these relationships; however, the film does not give them the time of day, preferring instead to plod along, confusing and frustrating in equal measure.

There are also issues in terms of storytelling. The use of captions to provide information rather than expositional dialogue can work in the cases of historical epics, but here, especially in one particular instance, they actually work to the film’s detriment. When the army reaches the Harran village, there has been no mention of cursed tribes, and the wolves we have seen up to that point have never provided any real threat or menace, but the caption appears on screen to tell us the rumour of a curse upon the tribe. Had this information been delivered earlier in the proceedings then perhaps it would have been cause to fear the army’s arrival. As it is, when they reach the village, we are given the information we need on the screen, so all sense of tension and any wonder of the supernatural is lost - it feels as though we’re starting all over again in a different film.

There are some very important themes to be found at the heart of this film. The idea that man is little more than a beast, and his actions lead only to de-evolution or death is a strong central premise, but it takes some effort to see this clearly through the landscape Zhuangzhuang has created. By the time the final confrontation occurs, it is obvious what is going to happen, but, by then, it’s difficult to care, as there has been no effort made to bond us with the action and the characters on screen resulting in what should have been a very personal and moving experience feeling superficial and strained.

Not awful by any means, but a difficult film to sit through. The ideas are there, but their execution is handled a little awkwardly. While it’s always nice to see the majestic Chinese landscape in all its glory, it would be nicer to have it populated by fully developed characters and an engaging story to match. RM

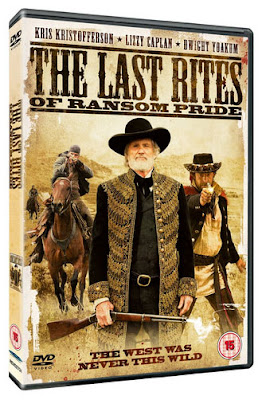

SPECIAL FEATURE: DVD Review: The Last Rites Of Ransom Pride

Film: The Last Rites Of Ransom Pride

Year of production: 2010

UK Release date: 30th May 2011

Distributor: Revolver

Certificate: 15

Running time: 79 mins

Director: Tiller Russell

Starring: Dwight Yoakam, Lizzy Caplan, Jon Foster, Cote de Pablo, Jason Priestley

Genre: Action/Drama/Western

Format: DVD

Country of Production: Canada

Language: English

Review by: Sarah Hill

The Last Rites Of Ransom Pride is the debut feature film of documentary maker Tiller Russell in which he aims to put a contemporary twist on the western genre. The film, which premiered at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 2010, was filmed in Canada with a modest budget of approximately $8 million.

In Mexico in the 1910s, outlaw Ransom Pride (Scott Speedman) is hunted down and shot after he kills a priest. His lover, Juliette Flowers (Lizzie Caplan), embarks on a mission to bring his body back home to Texas with the help of Ransom’s brother, Champ (Jon Foster).

However, Ransom’s body is being held by a Mexican Bruja (Cote de Pablo), the sister of the man he killed, as recompense, so Juliette offers to buy back Ransom’s body and soul with the blood of his brother. But the Pride brothers’ father, Reverend Pride (Dwight Yoakam), is determined not to let this happen...

Occasionally, a low budget film will overcome its limitations and acquire ‘cult’ status. The Last Rites Of Ransom Pride is not one of those films. The film attempts to establish itself as an edgy and contemporary western through its fast-paced, True Blood-esque opening credits. However, like much of the film, whilst Tiller’s intentions for the opening credits are clear, they miss the mark somewhat and are disorientating rather than impressive.

If the opening titles demonstrate anything about what is to follow, it’s that Tiller has a compulsive fascination with video-style jump cuts. This style of editing would work well if it was used sparingly, but Tiller makes the unusual and frustrating decision to recap the main events of every scene in a quick-fire, condensed form immediately afterwards, making the term ‘flashback’ seem all too literal. Furthermore, these ‘flashbacks’ are sepia-tinted to such an extent that they take on a muddy brown aesthetic. This is coupled with the fact that the scenes which take place in the present look overly grey and grainy. The film subsequently flits between the two aesthetics and, in doing so, prevents any sense of realism. Also, the film’s obligatory shoot-out is edited so frantically that looks more like a self-contained music video as opposed to a scene from a film.

The film’s lack of credibility is compounded by its two-dimensional characters. Bruja the witch doctor seems to remain in a permanent state of seething, spitting anger throughout the film, and the more ‘quirky’ characters such as The Dwarf, whose appearance borrows very heavily from Johnny Depp in the Pirates Of The Caribbean films, are not interesting enough to enable them to become good cult characters.

Lizzie Caplan, as Juliette, gives what is probably the best performance in the film, although this is no doubt aided by the fact that the other performances are very weak. Caplan’s dark and fierce eyes adequately convey Juliette’s determination to bring Ransom home for burial and she is obviously a very strong woman. It is disappointing, therefore, that when given the chance to subvert convention by creating a strong female protagonist, in what is traditionally a very masculine genre, Juliette Flowers is frequently presented as little more than a sex object. She also makes some disappointingly obvious, yet uncharacteristic decisions throughout the film. For example, her decision to embark on a relationship with Ransom’s shy brother is a lazy plot device and arguably a decision that does not befit her character.

As well as being rather obviously plotted, the film’s dialogue is also very clunky and clichéd. When ordering his men to track down and kill Juliette, Reverend Pride says that he doesn’t care what they do to her, but just “make sure she ain’t breathing when you’ve finished.” Similarly, the closing line of the film, a quote from Ransom Pride himself, is equally as banal: “I was always a lover, despite the killings.”

It is clear that The Last Rites Of Ransom Pride wished to be thought of as a subversive western with cult status. However, whilst the film does contain impressive photography on the odd occasion - such as the fairly poetic shots of the sun shining over the plains - its infuriating over-reliance on flashy editing techniques, poor plot, uninspiring characters and clunky dialogue means that the film ruins any potential that it may have had. If the film teaches us anything, it’s that there is a fine line between a ‘cult’ film and a bad film, and, sadly, The Last Rites Of Ransom Pride belongs on the wrong side of that line. SH

REVIEW: DVD Release: World Without Sun

Film: World Without Sun

Year of production: 1964

UK Release date: 23rd May 2011

Distributor: Go Entertain

Certificate: E

Running time: 93 mins

Director: Jacques-Yves Cousteau

Genre: Documentary

Format: DVD

Country of Production: France/Italy/USA

Language: French (English dub)

Review by: James Garner

Jacques Cousteau is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of marine conservation, and his documentaries introduced millions of people across the globe to the wonders of aquatic life. World Without Sun proved to a be a huge hit following its release in 1964; fascinating audiences with its footage of seven oceanauts going about their daily lives in an undersea station and exploring the hidden depths of the Red Sea off the coast of Sudan.

Cousteau established his underwater base, called Continental Shelf Station Two, in order to further his studies of marine life and to see how men adapted to life on the ocean floor. He and his fellow oceanauts spent one month living in the structure, situated 10 metres beneath the surface.

Apart from the five-roomed main base, there was also an underwater hangar that housed a flying saucer-shaped yellow submarine, and a small ‘deep cabin’ in which two oceanauts lived in cramped confines at a depth of 30 metres for one week at a time. The entire operation was supported from above by a team based on Cousteau’s ship, the Calypso, but the sense of isolation is palpable, especially in the ‘deep cabin’, where there was barely any space to move around in, and the helium-rich air the men breathed caused them to sound like chipmunks.

The oceanauts encountered all manner of strange and beautiful sea creatures when they were diving in the surrounding waters and capturing sea life to study, but perhaps the most interesting part of World Without Sun is watching the men trying to establish a daily routine in the main base; drinking, eating, smoking, listening to music and playing with their pet parrot…

The machinery involved may look a little dated now, but it has a retro science fiction-esque charm made all the more absorbing by the fact that what we’re seeing is real. That said, at the time of its release, there were accusations from certain quarters that Cousteau had faked some of the footage, allegations that he vigourously denied.

Near the end of World Without Sun, we see the two-man submarine travelling to a depth of 300 metres and discovering an undersea cavern with a pocket of air. A camera outside the craft shows the hatch being opened, and an oceanaut inspecting the cavern without the aid of any breathing apparatus. Real, faked or partially staged, it’s an intriguing sequence that sparked debate among oceanographic experts at the time, some claiming that such a cavern with an air pocket is an impossibility.

What is clear, though, is that Cousteau was something of a showman, and was highly skilled at making complex scientific data accessible and easily comprehensible to ordinary viewers with limited knowledge of oceanography and marine life. Whether you think he faked footage in World Without Sun or not, it’s undeniable that Cousteau was a crucial figure in heightening awareness of marine life and the need for stronger conservation measures. That he did so with such style and gentle humour makes him even more effective and likeable.

In one scene that sums up Cousteau’s playful spirit very well, we see oceanauts threatening scallops with starfish, their natural predators, causing the scallops to gallop frenziedly across the ocean floor. It’s a little cruel, and probably isn’t the kind of interference that would be tolerated by 21st century marine biologists, but it is quite amusing nonetheless.

Wes Anderson’s 2004 comedy-drama The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou was inspired by his boyhood fascination with Cousteau, and the DVD and Blu-ray release of this mid-60s classic will hopefully encourage a new generation of viewers to acquaint themselves with the innovative work of the explorer, ecologist and filmmaker who died in 1997.

Apart from co-developing the aqua-lung, Cousteau pioneered filmmaking techniques that allowed him and his crew to capture life beneath the waves in incredible detail. In spite of being almost fifty years old, World Without Sun still looks spectacular, and still has the power to immerse viewers in a world increasingly under threat.

World Without Sun was the second Cousteau film to win an Oscar for best documentary feature, following the earlier success of The Silent World in 1956, and has stood the test of time remarkably well. Fascinating and compelling, it brings the mysteries of the deep into your living room. JG

REVIEW: DVD Release: Voyage To The Edge Of The World

Film: Voyage To The Edge Of The World

Year of production: 1976

UK Release date: 23rd May 2011

Distributor: Go Entertain

Certificate: E

Running time: 90 mins

Director: Philippe Cousteau

Starring: Jacques-Yves Cousteau

Genre: Documentary

Format: DVD

Country of Production: France

Language: French (English dub)

Review by: Calum Reed

“We are witnesses to the vanishing of an eternity,” Philippe Cousteau proclaims in the final breaths of his documentary, Voyage To The Edge Of The World, as his father, Jacques, reaches the end of his journey to the outer-reaches of the South Pole. Of all the faraway cultural landscapes and alien habitats open to exploration, Antarctica appears to be the en-vogue topic of the moment; Luc Jacquet’s March Of The Penguins chronicled the life cycle of its bird-dwellers, while more recently Werner Herzog’s Encounters At The Edge Of The World sees the renowned director ape the Cousteau family’s 1975 cross-continental trip. As mentioned in the film, this journey marks a two-hundred-year anniversary of explorer Captain James Cook’s crossing of the Antarctic Circle during his circumnavigation of the globe in the 18th century.

Despite Cousteau’s established attachment to the underwater world as an oceanographer, evident in his work for National Geographic, and Oscar-winning feature Le Monde du Silence, this marked the man’s most daring endeavour to date.

In 1973, Captain Cousteau set sail for Antarctica in his boat, Calypso, accompanied by a crew that included his son Philippe, a previous collaborator and partner on TV series The Undersea World Of Jacques Cousteau. The film follows the Cousteau and the Calypso from the time that it arrives at the South Pole to the end of the exploration of its waters.

While a prolific filmmaking duo during their time together, Philippe would work with his father just one more time after Voyage – in their search for the lost continent of Atlantis – before a boat crash caused his untimely death in 1979, at the age of 39...

While primarily an ode to the South Seas and their unorthodox array of creatures, Voyage To The Edge Of The World is just that – a voyage – and it manages to convey the sense of journeyman in Cousteau et crew particularly well given that there isn’t a diary-structure as such. One of its most appealing attributes is that Philippe Cousteau doesn’t get too over determined with creating a compelling narrative outside of marine life and glacial terrain. But for a brief segment where he mourns the tragic accidental loss of Michel Laval, the ship’s second-in-command, the emphasis is always placed upon gaining insight into a world we know relatively little about – especially considering that this occurred nearly forty years ago. When Philippe does attempt to inject drama, it’s usually through presenting the landscape as a hurdle for the expedition; the group must first navigate an active volcano and later navigate a pool of icebergs in order to progress safely.

What’s achieved is largely through exercising a patient approach, understated up to its euphoric final moments, even as Philippe pertains to include swooping aerial shots and a graceful musical score. Father and son also alternate between providing voiceover commentary, resisting literary intonation in favour of a more practical impression of the place. The aesthetic qualities of Voyage To The Edge Of The World lie in its faithfulness to the sea – perhaps not surprising, as both father and son are proven pioneers in the field of documentarianism. Their welcome desire to leave this distant climate unimposed allows the forays into penguin behaviour and deepwater organisms to provoke their own inherent allure and magic; the Cousteaus project romantic ideas onto Antarctica, but don’t purport to be above their station as fledgling voyagers. They remain incredibly respectful of it as a haven for sailors, naturalists, enthusiasts in its untouched state.

Above all, Cousteau creates the impression of Antarctica as a tranquil odyssey, aided heavily by editor Hedwige Bienvenu’s fluid, assured style. While Voyage To The Edge Of The World wanes a little in interest in the middle section, that’s more a result of pedantic explanation of processes than it is of the film’s diminishment as a visual showpiece. It’s pieced together with loving delicacy and thoughtful flair; a stripped-bare, simplistic presentation of life in the South, and a reservedly charming engagement with the natural world. As the film builds towards an underwater climax, Cousteau and crew’s passion for this unknown corner of the world is felt – without the need for heavy personalisation or dramatic camerawork.

Serenely mastered, Voyage To The Edge Of The World is Cousteau’s love letter to nature; in particular, the mystery and metaphysics beneath Antarctica’s oceanic expanse. It’s a modestly-played documentary designed more towards developing intrigue through a meditative comb of the location rather than an exciting adventure story, and surely succeeds in opening our eyes to the mystical beauty of a wilderness and the settlers who inhabit it. More concerned with the power of imagery than a need to educate and inform, the film finds a median between postcard admiration and spiritual fascination in detailing – what many believed to be – the point at which civilisation ceased to exist. CR

REVIEW: DVD Release: The Silent World

Film: The Silent World

Year of production: 1956

UK Release date: 23rd May 2011

Distributor: Go Entertain

Certificate: E

Running time: 86 mins

Director: Jacques-Yves Cousteau & Louis Malle

Genre: Documentary

Format: DVD

Country of Production: Italy/France

Language: French

Review by: Rob Ward

Having inspired swathes of oceanographers and documentary makers from Steve Zissou to David Attenborough, Jacques Cousteau was a true trailblazer in the world of underwater filmmaking. And now, more than fifty years after its initial release, this groundbreaking feature is available for home audiences on DVD and Blu-ray. But in the face of modern technology and filming techniques, can Cousteau’s 1954 Oscar winner still hold its own?

Set on board the good ship Calypso, The Silent World follows Cousteau and co-director Louis Malle on their mission to capture the hitherto unseen beauty of the deeps on camera.

Filmed in glorious Technicolor, the film reveals the unseen world and a wealth of life which was brand new to the original audience.

Life on board the boat is both a voyage of discovery and an adventure, as the crew utilise aqualung technology to film deeper than ever before, capturing shark attacks, shipwrecks and a sense of boundless possibility…

The film opens with a stunning descent to the depths, as five bare-chested divers swim through a vivid blue expanse. Each carries a flaming torch, somehow burning despite being submerged. Huge gas plumes rise above them as the commentary announces that "this is a motion-picture studio 65 feet under the sea." It’s an intriguing opening, beautifully framed and impressive so many years after the event – largely because it leaves an audience accustomed to wetsuits and cutting edge diving equipment, wondering how it’s possible to survive and film at such depths with underwater flares and antiquated oxygen tanks.

The divers are compared to spacemen and it’s easy to see why. Their movements are not typically human and their environment is utterly alien. With the seabed illuminated by large floodlights, the blue water is punctuated by corals and crustaceans of bright reds and oranges – a natural contrast to the burning orange flares which previously lit their way. But upon surfacing, the crew become merely human again. And their humanity is in stark contrast to the natural beauty they left below the ocean’s surface.

Cousteau is a bronzed, hard-bodied figure. His leathery skin and lean frame make him look rather like one of the sea-creatures he seeks to film – and he’s seemingly less comfortable on deck than he is underwater. Despite giving a fascinating insight into the cameras and filming apparatus which allowed their early forays beneath the waves, it is the ethical and environmental choices made by Cousteau and his crew which jar with a modern audience.

Despite describing the ‘50s as a “golden age” for underwater exploration, much of Cousteau’s aim in this film seems to be the exploitation of the natural resources. Perhaps hindsight and greater knowledge of the natural world are responsible for the uncomfortable feeling which accompanies watching a man hitching a ride on a turtle or dynamiting a coral reef, but it’s impossible to imagine that someone as well versed in the relationship between mankind and marine life failed to realise how wrong it is to interfere in such a way. And such misgivings are nothing compared to those which accompany the film’s most disturbing scene...

Following a huge pod of sperm whales, the Calypso follows them through the ocean. Sadly, a young calf is pulled under the boat and into its propellers. Bleeding heavily, it is unlikely to survive, so Cousteau makes the decision to pull it alongside the ship and put it out of its misery by shooting it. The water around the ship is red with blood and, predictably, begins to attract sharks. These scavengers of the sea tear the whale to pieces. Whilst this might be difficult for some viewers to watch, it is not nearly as uncomfortable as seeing the Calypso’s crew dragging these sharks onto the boat’s deck and hacking at them with axes and crowbars.

It’s a sickeningly unnecessary display of vengeance. But what are they seeking revenge for? Animals attacking and eating an animal which has already died – and at their hands? Whilst the footage is dramatic, it is utterly contrived and completely barbaric. It serves no purpose, and even their relative lack of knowledge cannot defend them against accusations of opportunism and bloodlust.

Punctuating the documentary are some truly excruciating scenes of ‘faux reality’. Much like those seen in reality TV pap like The Only Way Is Essex, The Silent World features some heightened versions of reality. Rehearsed and acted, these come across as being uncomfortable and unnatural for everyone involved. It’s a shame that the conventions of the time didn’t allow for a more realistic portrayal of everyday events – the watching audience would have been afforded a much more interesting window into the truth of Cousteau’s adventures were it not for these parodies of reality.

There are some wonderful episodes, though. A pod of dolphins is captured playfully swimming alongside the Calypso, and an underwater wreck is explored in exquisite and understated detail. Combined with Cousteau’s infectious (although often misplaced) enthusiasm, this ensures that there is enough of interest here to ensure that it remains a historically and cinematically interesting piece.

The Silent World is little more than a period piece, serving to remind us how far our knowledge and understanding of the natural world has developed in the last half century. Whilst Cousteau shone a light on how fascinating life in the oceans is, he never really illuminated it. That this was due to ignorance or the lack of necessary technology is a moot point: whilst we have the likes of the BBC producing nature programmes like The Blue Planet, we will only ever need to view Jacques Cousteau as relic and a reminder of how far we’ve come. RW

REVIEW: DVD Release: Psalm 21

Film: Psalm 21

Year of production: 2009

UK Release date: 30th May 2011

Distributor: Revolver

Certificate: 15

Running time: 114 mins

Director: Fredrik Hiller

Starring: Jonas Malmsjö, Niklas Falk, Björn Bengtsson, Görel Crona, Josefin Ljungman

Genre: Horror/Sci-Fi/Thriller

Format: DVD

Country of Production: Sweden

Language: Swedish

Review by: Matthew Evans

The debut film of Swedish director Fredrik Hiller, Psalm 21 is a horror film with ambitions. Sure, it features many a decaying ghost and a man with a haunted past – core staples of any horror film – but it also has a chip on its shoulder; Mr. Hiller has a bone to pick with religion.

The film tells the story of Henrik Horneus (Jonas Malmsjo), a Christian priest who lives his life by the words of the New Testament. When Henrik learns of his father's death from an apparent drowning accident, he decides to travel to the isolated village in which his father's body was found. However, his arrival and subsequent suspicion as to the true circumstances of his father's death set Henrik on a collision course with his past - a past he would much rather forget.

In his quest to solve the mystery of his father's death, Henrik finds himself haunted – quite literally – by the ghosts of his past. As the truth finally outs, Henrik battles to save himself from his own personal hell and, in the process, learns a few home truths about the religion which he holds so dear...

Angry Biblical texts and gruesome ghosts with a propensity to scream at passersby abound, Psalm 21 doesn't give itself all that much to work with. In the style of many horror films before it, Psalm 21 is a rather mundane 'who done it' murder mystery, dotted with supernatural goings on and a few cheap camera tricks. What's more, it has an agenda, and it's intent on ramming it down your throat.

At first glance, the film looks rather promising; Asian horror has quite clearly influenced much of Psalm 21's style. Washed out colours and decent special effects combine to give the film a moderately eerie feel. However, the plausibility of the film is abruptly shattered the moment Jonas Malmsjo opens his mouth.

The film's contrived dialogue is not only unconvincing but, in many cases, laughable. This is demonstrated in the scene where Henrik learns of his father’s death, in which Malmsjo's performance fails to convey any consistent emotion. From an ice cold glare to a wobbly lipped murmur to a hysterical fit of laughter, Henrik comes across as somewhat of a psychopath, rather than a character with which one could sympathise. The intention of this scene is, of course, to convey Henrik's haunted past and his mixed emotions when confronted by his father's death. Instead, Henrik comes across as somewhat of an oddball.

Sadly, the performances on offer merely highlight the film's other failings; primarily its script. Psalm 21 trundles along for most of its duration, apparently content with its generic 'murder-mystery' script, and if it had continued along this path it might warrant some small degree of respect. However, things take a rather unexpected turn as we reach the film's climax. In a rather unexpected move, the director goes about voicing some of his thoughts on organized religion. As many of his opinions had been more subtly expressed throughout the film, this really was a silly move. The fact that Fredrik Hiller felt the need to ram his views down the throats of his audience merely demonstrates the weaknesses of his film.

Long gone are the days when a director could get away with producing a successful horror film with a few cheap camera tricks. You are fooling no-one by hiding a decaying child behind a bathroom door or having ghosts miraculously appear as a camera circles a character in a 360 degree shot. Fredrik Hiller is mistaken if he thinks a few cheap scares, a handful of CGI ghosts and controversial statement on religion will save him.

However, there are some positive aspects to Psalm 21's script. As mentioned above, for most of its duration the film does allude to the overarching message which it so painfully preaches during its closing scene. If it were not for this final scene, the film could be complimented on its interesting depiction of Henrik's personal hell. Even though every twist is clearly signposted, the script does offer brief hints of originality.

Psalm 21 is a rather disappointing, if not painfully predictable, addition to the horror genre. Whilst its script occasionally alludes to something deeper, acting as a denouncement of organised religion, it is undermined by the film's appalling closing scene. Sadly, terrible performances, forced dialogue and cheap camera tricks conspire to offer the crippling blow to this hellishly flawed film. ME

REVIEW: DVD Release: Agnosia

Film: Agnosia

Year of production: 2010

UK Release date: 30th May 2011

Distributor: Momentum

Certificate: 15

Running time: 106 mins

Director: Eugenio Mira

Starring: Martina Gedeck, Eduardo Noriega, Bárbara Goenaga, Félix Gómez, Jack Taylor

Genre: Crime/Drama/Thriller

Format: DVD

Country of Production: Spain

Language: Spanish

Review by: Daryl Wing

From the producers of two of the greatest scare-fests of recent years, Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and The Orphanage (2007), written by Antonio Trashorras, who also co-penned Guillermo del Toro’s spectacularly spooky The Devil’s Backbone (2001), and directed by Eugenio Mira, who brought us darkly comic The Birthday (2004), comes Agnosia, a Spanish period drama about love and, er, deceit? There must be some mistake, surely?

Joana (Bárbara Goenaga), a young woman suffering from the rare neuropsychological condition agnosia, which affects her sensual awareness, is preparing for her wedding to her father’s business associate, Carles (Eduardo Noriega).

Although Joana's eyes and ears function perfectly, her brain cannot interpret the stimuli she receives through them. When her father dies leaving behind a secret that only Joana knows, the formula to a telescopic lens hidden in her subconscious, she falls victim to a sinister plan to take advantage of her condition.

While her enemies try to extract the secret against her will, a handsome young man called Vincent (Felix Gomez), who previously worked for her father and shares an uncanny resemblance to Carles, is blackmailed into helping them, but his feelings toward Joana prove that perception isn’t always reality…

Eugenio Mira’s movie is wrought with persuasive period detail, lush landscapes, strong performances from an outstanding cast, but most surprising of all, razor-edged savagery and bursts of brutal imagery that make Agnosia almost as chilling as any of the movies already mentioned. It’s a genuinely refreshing surprise, even after the opening stampede when a horse is executed because they ran out of balloons. The plot veers into fantastical territory throughout, but Mira keeps it in check by allowing the characters to be as real as possible.

The opening act is quite bizarre, but all the better for it. Beginning many years earlier, when Joana is a child, the audience is able to revel in the film’s opulent surroundings reminiscent to countless fairytales as a group of wealthy gentlemen test out a new telescopic lens, shooting at balloons released by the whippersnapper. But then the horse gets one in the neck, a child collapses, the beginning of her suffering, and we are catapulted into a bleak, shadowy world controlled by villains and thugs. In turn, we are introduced to Vincent, ambushed and outnumbered, innocent yet insurgent, and the one man who can make Joana’s universe worth seeing again.

At its best, Agnosia is cruel and hard-hearted, with only Joana and her father decent enough to route for. The rest of the cast provide constant wickedness, whether it be Noriega’s reasonable turn as Carles, with his countless trips to the whorehouse because his future spouse isn’t giving him any (and he’s too polite to ask), or the mad doctor using his respectability to make lots of money, down to the evil business partner that never leaves loose ends, and even Vincent, a nice guy who doesn’t care if the girl he wants to ‘smash’ is getting married.

Because of this, there is bloodshed throughout. Not of the Sunday afternoon, Sikes murders Nancy variety, kindly gruesome even if it’s one of the most graphic, frightening scenes Dickens ever wrote, but seriously violent, and truly unexpected, whether it’s the death of a stallion, a servant - many servants - or the shy, unassuming Joana herself. A neat twist may propel us into act two, but the thrills witnessed here are not from the love triangle that slowly develops (although Joana’s conversation with Carles after spending a thunderous night with Vincent is comically tragic), but from the more believable world of corruption it’s set in.

Sadly, although it makes for convenient plot lubricant, the biggest stumbling block is the notion that Joana is unable to distinguish Carles from Vincent. And let’s face it, without this believability, the film is going to fail, no matter what else happens. It’s certainly difficult trying to suspend disbelief. With her impaired vision, his looks (although more youthful) are convincing, yet his voice, and the hope we can believe in a relationship that suggests they have barely touched each other since childhood, doesn’t quite wash. It’s a shame, because although both Vincent and Carles are likeable, there really should only be one winner.

Let’s face it, though, shoving a girl in a cocoon for three days and kidnapping her to retrieve the secret formula is a hard sell by anyone’s standards, as is the revelation during a pleasant period drama that it’s actually hidden in Joana’s subconscious, while the love story, despite its over-egged conclusion, is well executed and refreshingly realistic. Having witnessed the beauty that is Bárbara Goenaga, you would be lying if you didn’t understand either man’s plight. And so, with a barely noticeable soundtrack, which isn’t a bad thing, other than its clumsy hindrance to Vincent’s escape attempt, Agnosia fails to catch fire. To paraphrase Joana’s disappointment, “Last night, Agnosia, you seemed like someone else.”

As impressive as it looks, along with its surprising acts of brutality, Agnosia fails to convince because it can’t combine fairytale sweetness and quirky invention with realism where it really counts – a flawed but promising addition to Spanish cinema. DW

REVIEW: DVD Release: 5150 Elm's Way

Film: 5150 Elm's Way

Year of production: 2009

UK Release date: 30th May 2011

Distributor: Entertainment One

Certificate: 18

Running time: 110 mins

Director: Éric Tessier

Starring: Marc-André Grondin, Normand D'Amour, Sonia Vachon, Mylène St-Sauveur, Élodie Larivière

Genre: Drama/Horror/Thriller

Format: DVD

Country of Production: Canada

Language: French

Review by: Rob Markham

Captivity is a strong central premise in horror cinema. From the extreme gore of films like Hostel and Saw to the intense psychological torment of more thoughtful films such as The Ordeal, it is a path well-trodden in the genre. 5150 Elm’s Way (5150 Rue des Ormes) is a French-Canadian offering of that familiar beast, only choosing to use the brain instead of other, messier, internal organs.

Having just moved to attend film school, Yannicknick rides his bike around his new environment and documents the surroundings with his camera. Taking a ride to the suburbs, he turns down Elm’s Way, but comes off his bike and injures himself. Noticing a taxi parked outside 5150, he asks for a ride and the owner offers to call one for him as he is off duty.

Yannicknick enters the house uninvited to wash the blood off his hands, but hears a disturbing sound from upstairs and goes to investigate. He finds a man with a serious wound screaming for help.

Yannicknick tries to escape, but is forced at gunpoint to stay, and soon finds himself a prisoner of Jacques, a ‘righteous’, psychotic killer, and his dysfunctional family. Jacques has no choice but to keep Yannick prisoner until he can work out what to do with him and the strain soon takes its toll on the family unit.

Jacques offers Yannicknick the chance of freedom, but only if he wins at chess. The only problem is that Jacques is a champion chess player - and unbeaten...

There is a formula that many successful horror films (and in many cases, entire franchises) can follow in the captivity sub-genre: introduction, capture, torture, escape, redemption... It’s been proven to work over and over again, particularly with the advent of the dubiously named ‘torture-porn’ genre. You could be forgiven for thinking 5150 Elm’s Way would follow the same pattern.

It certainly seems that way when we first meet Yannicknick, a fresh-faced film student with a nice girlfriend. The first hints that things are not what they seem are laid out for us in the form of his alcoholic mother and generally disapproving and disappointed father. We follow Yannicknick for a while as he rides around his new neighbourhood, and we are shown just what a moral young man he is when he returns a young girl’s stolen ice-cream from a bully.

Fortunately, we are not made to suffer the usual clichés of the genre, even though when Yannicknick knocks on the door of 5150 Elm’s Way, we know exactly what will happen (the clue is in the title after all).

Instead of the usual green-lit, dirty basements, barred cages and dingy operating theatres, Yannick is imprisoned in an incredibly pleasant family home with pictures on the walls, children’s bedrooms complete with cuddly toys, and a generally comfortable feel to the place. This is starkly contrasted with the actual room of Yannick’s imprisonment, which is barren, with a plain floor, dirty walls, bloodstains and a mattress at one end. It is an effective use of mise-en-s cène and director Eric Tessier piles on the visuals to signify Yannick’s increasingly fragile state of mind. The most effective of which is the growing bloodstain on the wall. There are times when the effects seems a little overwrought (Yannick’s hallucinations, for example), but on the whole, Tessier does a good job in making us feel as confined as Yannick.

The family itself would give any student of psychoanalysis a headache, as we are faced with varying complexities and complex relationships. The father, Jacques, believes he is righteous and kills those he sees as evil. He also robs grave for the bodies of those he considers righteous, in order to complete a secret project (without wanting to spoil anything, it involves his passion for chess). The mother, Maude, is a religious and fragile creature, who is loyal to her husband but sees the wrong in what he does. Michelle has inherited her father’s propensity for murder, but she does not have the ideology that he does. Anne is a young, mute child who cannot disguise her contempt for her father.

There are certainly hints of Freudian themes, and, at one point, there seems to be an attempt at a representation of the Oedipal Complex, where Yannick has Maude believing they can have a life together, away from Jacques. Yannick’s own father issues also make their mark but aren’t given enough real depth for them to be effective. There is certainly enough to keep the most avid critic referring back to Freud and Lacan.

There are, in fact, a few too many issues to deal with in the family unit. So many that the running time cannot possibly give all of them the analysis they deserve. As a result, the family’s woes seem to be slightly superficial. As the film develops, we contend with the increasingly unbalanced Maude, the psychotic Michelle, whose inheritance of her father’s passion for righteousness is seriously misguided, Anne’s sectioning, and, of course, Yannick’s predicament in the room upstairs. This is a brief description of the dynamics. There is more.

Perhaps an attempt to focus on less of the various threads and to concentrate on developing only a few of them would have been more successful in terms of storytelling, but, as the film progresses, the tension does mount to great effect through the confrontations over a chess board between Yannick and Jacques. Chess becomes a shared of obsession and the film almost plays like a chess match itself, building piece by piece until the climax. It is an effective technique, and the performances do it justice.

Unfortunately, there are too many contrivances throughout and by the end it feels forced. The journey of Yannick’s taped plea for help borders on ridiculous to the point where you could be forgiven for thinking there are only three families living in the whole town. The character of Anne and her role in events is not given anywhere near enough development, and her involvement in the tense final scenes does not work as one would have hoped.

There are also some discrepancies; for example, Jacques insistence that the death of someone evil should be painless and quick, yet why does Yannick find a screaming, partially disembowelled man in the house? It also borders dangerously on the absurd, but there are enough positive points that it is well worth a watch.

A decent film, offering some interesting characters and direction. There is nothing particularly new here, but Tessier’s use of visuals and some great performances make for an entertaining thriller. If you’re expecting horror you may be disappointed. This is more of a horrific drama, but the tension is there. Perhaps it could have been more focused, but there is enough here to appeal to those with a penchant for the darker things in life. RM

REVIEW: DVD Release: Blind Date

Film: Blind Date

UK Release date: 23rd May 2011

Distributor: Network

Certificate: 15

Running time: 170 mins

Director: Stanley Tucci & Theo van Gogh

Starring: Renée Fokker, Peer Mascini, Roeland Fernhout, Wouter Brave, Jan Jaspers

Genre: Comedy/Drama/Romance

Format: DVD

Country of Production: Netherlands/USA/UK

Language: Dutch/English

Review by: Calum Reed

Those mystified by the attempts of the characters in Lars von Trier’s Antichrist to deal with the grief of their dead child may be equally puzzled by Dutch director Theo van Gogh’s 1996 film, Blind Date. Like the currently-troubled Dogme founder, van Gogh’s reputation as a cinematic provocateur caused controversy, reaching its peak in his critique of the treatment of female Muslims in 2004 short film, Submission. While von Trier’s recent behaviour at Cannes may lead to him becoming somewhat of a pariah on the festival circuit, van Gogh faced an eminently more dangerous opposition to his work: less than two months after Submission aired on television, he was assassinated by a Muslim extremist.

Blind Date opens with Renee Fokker’s Katja entering a rather tacky-looking lounge bar, in which she proceeds to first order a drink, before, secondly, making an enquiry of the whereabouts of Pom (Peer Mascini). As it happens, Pom has answered her advertisement in the personal columns for a “sweet, honest man” considerably older than herself, and as the two have dinner, they engage in the kind of small talk you’d expect from people meeting for the first time. What quickly becomes apparent is that these two are not meeting for the first time, and as their exchange accelerates towards a more volatile tone, we learn that they are actually married, and are heavily resentful of how their lives have turned out.

The film is divided into chapters based upon the personal ads, which are often shifting in nature according to what Katja and Pom want to learn from each other. As they constantly redress their desires, they discuss the reasons for their marital estrangement – nameably the death of their daughter in a car crash, and the implications of that event on their sexual relationship. During the course of Blind Date, they each adopt interrogative and submissive roles; including he as a reporter and blind man, and she as a psychologist and dancer…

Scissors and clamps are, thankfully, deemed unnecessary for this project about a couple trying to surmise what their marriage means anymore, but that doesn’t make these parents any less radical in their method of confronting harsh realities. As a conceptualised view of self-imposed ‘marriage therapy’, Blind Date holds weight: how to resolve a marriage where both parties can’t be in the same room together without relinquishing their identities? The nature of this coping technique, as a manufactured paradox of escape and confrontation, creates intrigue, and the tense interplay between Fokker and Mascini offers a tentatively balanced dynamic to all of their roleplays. The schematics of the film as a confessional, insidiously motivated acting duel inevitably leads to bouts of self-consciousness, but this doesn’t particularly hamper it until the later scenes.

Since most of Blind Date is essentially acting as a divulgement of exposition, it commands attention while things feel relatively fresh, but when the film runs out of backstory to reveal (and interesting ways to reveal it), the exercise becomes rather stagnant and roundabout. An intermittent voiceover accompaniment by the couple’s dead daughter adds to the extremely macabre humour intoned in some of the more sensationalist crevices of the script, as she launches into critiques of how they’ve behaved after her demise. It’s a device that feels far too facetious for a film that’s banding around so much emotional baggage, and a weak move to realise the daughter as a proponent of the present rather than the past.

While a far more seasoned veteran of the acting branch, Stanley Tucci has tried his hand at directing no less than four times, the most successful of which is Big Night, his 1996 collaboration with Campbell Scott. Tucci’s decision to remake the late van Gogh’s film in 2007 provoked surprised intrigue, and the following year it had its North American premiere at the Sundance Film Festival. While essentially a faithful remake, Blind Date (2008) doesn’t copy the original shot-for-shot, altering the sequence of events slightly to make more sense of the couple’s actions. Tucci also elects to alter the names of the central characters to Don and Janna, casting himself in the former role and Patricia Clarkson to star opposite.

Those familiar with Tucci and Clarkson’s recent partnership as Emma Stone’s easy-going parents in teen comedy Easy A will likely be a little aghast at how far removed from that wheelhouse Blind Date requires them to be. As two actors particularly excellent at instilling characters with natural qualities, this warring couple (no less conceited in nature than in the original) are far too alien and ugly for this acting duo to get to grips with. Playing against-type, the two expose the script’s manipulation of emotion far more than is present in the original - its dialogue falling flat with the familiar, composed actors unconvincing in alluding to the hatred and contempt Mascini and Fokker assumed in its predecessor.

The failure of Tucci’s version isn’t particularly consigned to either acting or casting errors, but reads as more of a misjudged endeavour entirely to take on a project that feels so heavily a product of its then-director. Van Gogh can coax some tremendous moments from his two stars because he’s so heavily involved in its authorial elements; while Tucci remains a sure admirer of the original (even tinkering with it somewhat), he’s still primarily an onlooker staging a reconstruction.

If 1996’s Blind Date was an experiment with mixed degrees of success, its descendant is an ill-conceived stab in the dark. Van Gogh introduced a gimmick capable of luring an audience into a state of studious fascination, but even then that gimmick didn’t have the legs to last eighty minutes. It’s unsurprising, then, that the mishandled remake feels like even more of a drag – loaded with two of the finest actors of their generation, but who are completely unsuited to the darker, and, frankly, bizarre complexities of this particular story. However seedy it sounds, one wishes there were more columns in the vein of ‘Man Seeks Less Talk And More Action’, since a dearth of impact is the chief common denominator between the two episodes. CR

REVIEW: Blu-ray Only Release: Salon Kitty

Film: Salon Kitty

Year of production: 1976

UK Release date: 30th May 2011

Distributor: Argent

Certificate: 18

Running time: 132 mins

Director: Tinto Brass

Starring: Helmut Berger, Ingrid Thulin, Teresa Ann Savoy, John Steiner, Sara Sperati

Genre: Drama

Format: Blu-ray

Country of Production: Italy/West Germany/France

Language: Italian/English

Review by: Mark Player

Italian filmmaker Tinto Brass has always been a controversial figure within European cinema due to his shameless and unorthodox depictions of the flesh. However, it is perhaps his first erotica film, the Nazi flavoured Salon Kitty (1976), that remains the most transgressive. Heavily censored when first released thirty-five years ago, Argent Films has reinstated and digitally restored Brass' original director's cut for a new Blu-ray release.

When war is declared between the Allies and the Axis powers, Kitty Kellermann's (Ingrid Thulin) high class brothel, Salon Kitty – a popular spot for soldiers, officers and dignitaries of the Reich – is appropriated by the Nazi government for military use. However, in exchange, a high ranking SS official by the name of Wallenberg (Helmut Berger) offers Kitty new premises, as well as a new staff of girls from Aryan stock; rigorously selected based not only on their appearance and sexual liberation, but their political beliefs. Kitty reluctantly accepts Wallenberg's gesture and, soon enough, business is back to normal.

However, unbeknownst to Kitty, Wallenberg has had the new building secretly wiretapped, documenting the pillow talk of party officials who feel that they can let their guard down and say what they really think about the war effort. Wallenburg's girls are also asked to dutifully record their encounters in written reports.

Complications arise when one of the girls, Margherita (Teresa Ann Savoy) – the subject of much perverse fascination for Wallenberg – begins to realise the extent and consequences of her duties when a disgruntled client (Bekim Fehmiu), whom she starts to fall in love with, is eliminated because of his anti-nationalist views...

After initially making shorts and avant-garde features, Salon Kitty was originally offered to Brass as a quick director-for-hire job. Brass accepted, but heavily rewrote the meagre initial concept to incorporate a more politically conscious angle. Strangely, this extra effort to make Salon Kitty more than just another skin-flick feels completely absent. Loosely based on real-life events (the Salon Kitty actually did exist during the late-30s, early-40s and was used for espionage purposes by the SS on their own men), Salon Kitty could've been an intriguing history lesson about the paranoid and volatile nature of the Nazi party's inner-sanctum with some erotica thrown in for good measure. However, this is not the case; the end result being a very long and tedious exercise in overt and senseless naughtiness.

The narrative is robbed of its potential by being not as prominent as a narrative should be. It's not so much placed on the back seat, but in the boot of a completely different car that's heading in the opposite direction. Only the barest glimmer of plot remains, acting as little more than a flimsy pretext for a revolving line-up of SS orgies, nude Nazi-saluting nubiles and other bizarre sexual practices, including a fat middle-age man fellating a phallus made out of bread placed between a girl's legs, to name just one. On that note: Wallenburg's selection process for the would-be whore candidates – some of which was originally cut but now reinserted – is also unorthodox and provocative; pairing the girls off with undesirable sexual partners – a hunchback midget, a Jewish POW, an amputee without legs – to prove their loyalty to the party.

The camera pervily leers and fixates on the skin and (often aroused) genitals of both genders in a seemingly never-ending series of wonky pans and zooms; clumsily spliced together by Brass, who insists on editing all of his films. There is a complete lack of rhythm, and sometimes purpose, from one cut to the next. Some shots last for half a second before being replaced by a fast moving zoom, creating an often frenetic and disorientating effect, designed to be impressionistic but instead feeling inappropriate and amateurish.

Due to excessive and dodgy dubbing into English, performances are difficult to gauge fairly and are laughably bad in places. Ingrid Thulin's involvement in a production like this seems very strange considering her many successful past collaborations with Ingmar Bergman – Wild Strawberries (1957), Winter Light (1961), The Silence (1963) and Cries And Whispers (1972) to name just some – and is given little to do, save for a handful of song and dance numbers, which feel like blatant padding and are somewhat unspectacular. Berger's Nazi official borders on the caricature, spewing terrible lines, whilst Savoy and Fehmiu make for a truly boring screen couple, which wouldn't be as much of a problem if so much time wasn't spent watching their reflections lounge about in bed post-coitus, speaking nothing of value.

The only intriguing prospect in all this pointless titillation is the reinsertion of previously removed footage. These new scenes haven't been dubbed into English, retaining their original language, making it pretty easy to identify what was omitted when the film was first released. On the downside, all this extra footage makes the film even longer – over two hours – which is perhaps Salon Kitty's biggest problem. A streamlined edit of eighty or ninety minutes would've been more bearable, although this wouldn't stop Salon Kitty from being what it is; a shameless exploitation piece that's not particularly interesting, or well made for that matter. Another deal-breaker for many will be a random abattoir scene towards the start in which live pigs are killed and decapitated for absolutely no reason in relation to the plot, but much to the delight of the people on screen.

As for the Blu-ray presentation: don't expect any spectacular visual overhaul or demo worthy presentation. The restorers have done their best with a clearly knackered source and, undoubtedly, despite the film looking every day of its thirty-five year vintage, this is the best Salon Kitty has ever looked on home video. Detail is adequate but not stunning. Colours fluctuate on occasion - one outdoor scene in particular has very noticeable shifts - many within the same shots. There are no overly visible compression artefacts to worry about, resulting in a decent presentation overall.

Salon Kitty is one of Brass' oldest and longest efforts, and one of cinema's true curiosities. A better film is potentially lurking in here somewhere but the mildly interesting set-up is cast aside in favour of copious and laughably gratuitous shenanigans. Fans of Brass' oeuvre will probably find more value here, but, for everyone else, it’s possibly only good for an ironic chuckle over how preposterous it all is. MP

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)