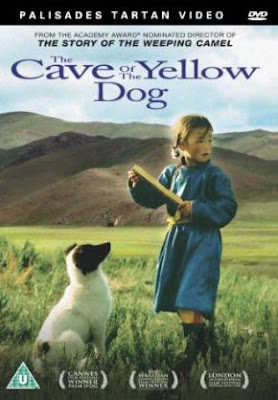

Film: Cave Of The Yellow Dog

Release date: 5th July 2010

Certificate: U

Running time: 93 mins

Director: Byambasuren Davaa

Starring: Batchuluun Urjindorj, Buyandulam Daramdadi, Nansal Batchuluun, Nansalmaa Batchuluun, Babbayar Batchuluun

Genre: Drama

Studio: Palisades Tartan

Format: DVD

Country: Germany/Mongolia

The director of The Story Of The Weeping Camel takes a different look at life in the Mongolian wilderness, having previously followed a family of nomadic shepherds and their camels to award-winning success.

Meet the Batchuluuns. They’re outdoor types - which is just as well, as they lead a nomadic existence as livestock farmers in the mountains of western Mongolia. There’s father and mother and their three young children – and, yes, there will soon be a dog.

The eldest daughter, Nansal, returns to the family yurt, from her urban boarding school, to much parental anguish. Wolves have killed two of their precious sheep and, from talking to other farmers in the area, it’s clear to the family this is an ongoing threat. With an increasing number of farmers moving to the towns in search of a ‘better’ life, there are fewer and fewer people to keep watch over any sheep. Suffice to say that Mr and Mrs Batchuluun are concerned about the future.

So, father is not best pleased when Nansal returns from a fuel-gathering trip one day with a small white dog in tow. She names him Zochor (Spot) – how comforting that dogs’ names, at least, cross cultural boundaries. “It has probably lived with wolves and will either kill our sheep or lead the wolves right to them,” says father. Heading off to town on his motorbike, to sell the skins of the two sheep, he makes it clear to Nansal he wants the dog gone by the time he returns.

Nansal, however, is not so easily persuaded – already it’s clear she’s a tough, smart, determined kid, growing up with an insatiable curiosity about the world around her. Out tending the herd one day on horseback – just one of many ‘adult’ responsibilities she must undertake from an early age – she is distracted, loses Zochor and gets lost herself searching for him. Finding Zochor just as its getting dark, with a storm breaking, she takes refuge with her grandmother in her yurt.

Her grandmother tells Nansal about the legend of the Cave Of The Yellow Dog. Suitably impressed, Nansal is finally reunited with her anxious mother who has come out looking for her in the darkness. Along with relief, we’re left with the feeling that it can’t be easy keeping your eye on your children in a playground that extends hundreds of miles into the wilderness…

What follows these early scenes is an extraordinary insight into the lives of this resourceful, loving family. Their very existence brings new meaning to the phrase ‘sustainable living’. Every day they must battle the elements, gather fuel, guard the sheep and themselves from wolves and vultures, create food from what they have around them (there’s an impressive lesson in cheese making from mother) and knock up the odd dress from scratch on the sewing machine. And then, of course, there’s the changing seasons – which means moving to new grazing areas. The dismantling of the yurt is a fascinating process – as is the packing of all their worldly goods onto oxen carts (and with three children, a house and a herd to take with them, they don’t travel light), and the heading off, literally, to pastures new.

But life’s not all uphill – there are many heartwarming moments between parents and offspring. Mother in particular seems keen on bestowing some philosophical wisdom on her eldest. “Stretch out your palm tight in front of you and try and bite it,” is one bit of curious advice she gives the child while slicing cheese one day. “I can’t!” protests Nansal. “There you are, then,” replies her mother. “Even when things are right in front of us, we can’t always have them.” With her grandmother, Nansal is curious about reincarnation. “Could I come back as a child?” she asks her. “See those grains of rice falling into the pot?” comes the reply, “try and land one on the tip of that needle.” Failing the impossible task, Nansal is advised “And that’s how hard it is to come back as a child.” Between her mother and her grandmother, young Nansal has a lot of wisdom to digest.

Whether or not you’ve seen Weeping Camel, this story stands proudly as a parable of life’s possibilities and limitations, and how we must all come to terms with them – wherever we live. Yes, the plot is fictional but the family – and their environment – is real. Nansal’s natural performance is particularly impressive at such a young age – her resourcefulness and charm bestow an irresistible screen presence. And, for their part, the parents contribute a nicely judged supporting role, revealing just what it takes to bring up a family in the wilderness. And the dog? Oh, yes, he’s cute. You can see why Nansal wants to keep him.

A delightful, fascinating and thoughtful docu-drama that will stay with you long after those dramatic mountain scenes have faded from view. CS

Meet the Batchuluuns. They’re outdoor types - which is just as well, as they lead a nomadic existence as livestock farmers in the mountains of western Mongolia. There’s father and mother and their three young children – and, yes, there will soon be a dog.

The eldest daughter, Nansal, returns to the family yurt, from her urban boarding school, to much parental anguish. Wolves have killed two of their precious sheep and, from talking to other farmers in the area, it’s clear to the family this is an ongoing threat. With an increasing number of farmers moving to the towns in search of a ‘better’ life, there are fewer and fewer people to keep watch over any sheep. Suffice to say that Mr and Mrs Batchuluun are concerned about the future.

So, father is not best pleased when Nansal returns from a fuel-gathering trip one day with a small white dog in tow. She names him Zochor (Spot) – how comforting that dogs’ names, at least, cross cultural boundaries. “It has probably lived with wolves and will either kill our sheep or lead the wolves right to them,” says father. Heading off to town on his motorbike, to sell the skins of the two sheep, he makes it clear to Nansal he wants the dog gone by the time he returns.

Nansal, however, is not so easily persuaded – already it’s clear she’s a tough, smart, determined kid, growing up with an insatiable curiosity about the world around her. Out tending the herd one day on horseback – just one of many ‘adult’ responsibilities she must undertake from an early age – she is distracted, loses Zochor and gets lost herself searching for him. Finding Zochor just as its getting dark, with a storm breaking, she takes refuge with her grandmother in her yurt.

Her grandmother tells Nansal about the legend of the Cave Of The Yellow Dog. Suitably impressed, Nansal is finally reunited with her anxious mother who has come out looking for her in the darkness. Along with relief, we’re left with the feeling that it can’t be easy keeping your eye on your children in a playground that extends hundreds of miles into the wilderness…

What follows these early scenes is an extraordinary insight into the lives of this resourceful, loving family. Their very existence brings new meaning to the phrase ‘sustainable living’. Every day they must battle the elements, gather fuel, guard the sheep and themselves from wolves and vultures, create food from what they have around them (there’s an impressive lesson in cheese making from mother) and knock up the odd dress from scratch on the sewing machine. And then, of course, there’s the changing seasons – which means moving to new grazing areas. The dismantling of the yurt is a fascinating process – as is the packing of all their worldly goods onto oxen carts (and with three children, a house and a herd to take with them, they don’t travel light), and the heading off, literally, to pastures new.

But life’s not all uphill – there are many heartwarming moments between parents and offspring. Mother in particular seems keen on bestowing some philosophical wisdom on her eldest. “Stretch out your palm tight in front of you and try and bite it,” is one bit of curious advice she gives the child while slicing cheese one day. “I can’t!” protests Nansal. “There you are, then,” replies her mother. “Even when things are right in front of us, we can’t always have them.” With her grandmother, Nansal is curious about reincarnation. “Could I come back as a child?” she asks her. “See those grains of rice falling into the pot?” comes the reply, “try and land one on the tip of that needle.” Failing the impossible task, Nansal is advised “And that’s how hard it is to come back as a child.” Between her mother and her grandmother, young Nansal has a lot of wisdom to digest.

Whether or not you’ve seen Weeping Camel, this story stands proudly as a parable of life’s possibilities and limitations, and how we must all come to terms with them – wherever we live. Yes, the plot is fictional but the family – and their environment – is real. Nansal’s natural performance is particularly impressive at such a young age – her resourcefulness and charm bestow an irresistible screen presence. And, for their part, the parents contribute a nicely judged supporting role, revealing just what it takes to bring up a family in the wilderness. And the dog? Oh, yes, he’s cute. You can see why Nansal wants to keep him.

A delightful, fascinating and thoughtful docu-drama that will stay with you long after those dramatic mountain scenes have faded from view. CS